In Retrospect

Friends We Never Knew

Tamanna Khan

26th March 1971

Aj Bangalin thaiy paar kadhya

Panhnji put je laash mathey

Janhn ji kachrri chaati cheehoon

Golee jo hee ghau disee

Porrhi maanas jo hanun jhurey tho

Rat mein lat pat nandhro bachro

Amaan chawe tho

Adh zaban wadhyal athas

Phathko phathko, nikre na sudko

Dam keean deay

(Extract from “March 2626 1971” a poem by Sindhi poet Anwar Pirzado.)

Over the dead body of his son, a Bengali mother is howling out of agony today,

Whose feeble chest is tattered by bullets that went deep,

And an old mother's whole being is sinking into abyssal pain.

Over there that small kid, soaked in blood, is trying to say, “mama”

Yet half his tongue is cut.

His breath is going high and high yet no tears in his eyes

Before his breath could break to finally end him,

His mama breathed her last.

(Translated by Javed Qazi)

|

Anwar Pirzado |

On March 26, 1971, in an oppressive prison cell in West Pakistan, a kindred soul of the Bengalis poured out his rage on a piece of paper. He had just received the news of the heinous massacre that the West Pakistani military regime had commenced on the freedom loving Bengalis on the dark night of March 25, 1971. Anwar Pirzado, a poet and journalist, was at that time serving sentence at the West Pakistani jail for treason.

Commissioned as a pilot of the Pakistan Air Force in 1970, Pirzado had written a letter to his friend saying, "Sheikh Mujib is a true leader for Pakistanis. Since he has won the election, power should be handed over to him peacefully. Otherwise the consequences will not be good."

The letter fell into the hands of the intelligence agency and immediately he was subjected to court- martial, terminated and sentenced to jail, informs noted Bangladeshi writer, filmmaker, journalist and activist Shahriar Kabir.

During his recent visit to Pakistan, Kabir, a member of the national committee to honour foreign nationals, in leading positions, who supported our Liberation War, came across Pirzado's story. Many voices like Pirzado's had flared up almost 1400 miles away in the enemy territory of West Pakistan, protesting and condemning the genocide of the Bengalis by the Pakistani Army in 1971. Among the more known poets whose verses breathed fire against the atrocities of the Pakistan military are Faiz Ahmed Faiz, Habib Jalib, Ahmad Salim, Sheikh Ayaz and Ajmal Kahattak.

Faiz Ahmed Faiz, one of the most celebrated Urdu poets, wrote “Hazar Karo Merey Tan Sey” (Stay Away from me (Bangladesh I)) in March 1971:

How can I embellish this carnival of slaughter? How decorate this massacre?

Whose attention could my lamenting blood attract?

There's almost no blood in my rawboned body

And what's left isn't enough to burn as oil in the lamp?

Not enough to fill a wineglass.

It can feed no fire,

Extinguish no thirst.

There's a poverty of blood in my ravaged body—a terrible poison now runs in it.

If you pierce my veins, each drop will foam as venom at the cobra's fangs.

Each drop is the anguished longing of ages' the burning seal of a rage hushed up for years.

Beware of me. My body is a river of poison.

Stay away from me. My body is a parched log in the desert.

If you burn it, you won't see the cypress or the jasmine, but my bones blossoming like thorns in the cactus.

If you throw it in the forests, instead of morning perfumes, you'll scatter the dust of my seared soul.

So stay away from me. Because I'm thirsting for blood.

(Translated by Aga Shahid Ali)

|

Waris Mir |

Since Faiz was a poet of international repute, just having won the Lenin Peace Prize, the Pakistani military junta did not dare libel him. However, Habib Jalib and Ahmad Salim were not so fortunate. Jalib was imprisoned and Salim jailed and sentenced to canning for writing poems against the genocide of Bangladesh.

A friend of Jalib recounted an anecdote to Shahriar Kabir in Lahore. “Towards the end of March, when the news of genocide was being broadcasted sporadically through the radio, Jalib and his friend had gone to a bar for an afternoon drink. Jalib told his friends 'it is a shame that while we are drinking ,our Bengali brothers are being butchered and our sisters are being tortured.' When a friend asked what they can do, he suggested that they bring out a procession in protest. Immediately, the seven or eight leftist poet in that group went out in the streets and started shouting 'Manzur Manzur Bangladesh Manzur' (Recognise Bangladesh),” relates Kabir.

Unfortunately, most of us in Bangladesh remained oblivious of these voices even after 40 years as the news of protest by West Pakistanis never reached the media. Shahriar Kabir explains, “At that time, the military regime of General Yahya Khan had imposed strict censorship on the entire media and prohibited any news of genocide from reaching the international arena.”

Reflecting on the situation of West Pakistan in 1971, Usman Qazi, former Central Vice President of Pakhtoon Students' Federation (a nationalist students' organisation following the non-violent mode of struggle for rights initiated by Khan Abdul Gahffar Khan) says, “There was such a blockade on information that people were largely unaware of the bloodshed taking place and the official version of 'a few Indian infiltrators causing trouble' was mostly accepted. A few of the Pakistanis found out the reality and shared it with the others back home and spoke up against the military action.”

Among them politicians and nationalist leaders belonging to the left wing were the foremost. They were closer to the facts of the events that followed the 1970 election, in which Sheikh Mujibur Rahman had won people's mandate to be the Prime Minister of the country.

Khan Abdul Wali Khan, President of the National Awami Party (Wali-faction) was one of those politicians. Wali Khan, son of the renowned Pashtun leader Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan, often known as the Frontier Gandhi, had sensed Bhutto's ill-intentions of siding with the military regime and ignoring the 1970 election results. Later, in an interview with the then AP journalist Arnold Zeitlin, he said, “I remember Bhutto said that it had been arranged with the 'powers that are' that in East Pakistan Sheikh Mujibur Rahman would rule, and in West Pakistan, Mr Bhutto would be the Prime Minister.”

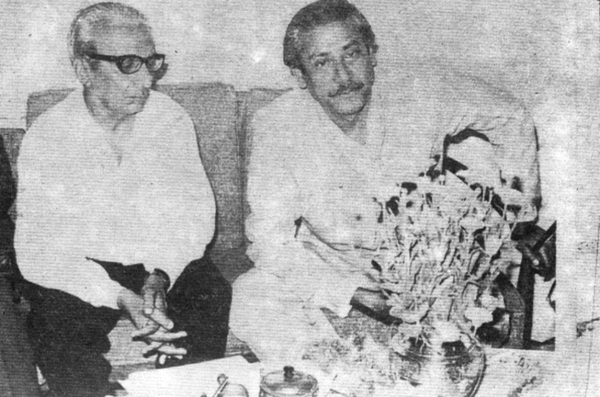

Qazi Faiz Mohammad with Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman.

Wali Khan's NAP had a stronghold at the North West Frontier Province of Pakistan that shares borders with Afghanistan. Jumma Khan, an old communist leader told Shahiriar Kabir that NAP had the responsibility to help those Bengalis who wanted to escape from West Pakistan. They would help them cross the border to Kabul from where they accessed the Indian embassy that gave them the necessary papers to return to safety.

Besides Wali Khan, Qazi mentions Balochi NAP leader, Mir Ghaus Bakhsh Bizenjo who accompanied Wali Khan in his effort to bring about a settlement between the Bengali and the West Pakistani military junta, before the crackdown began on March 25. Bizenjo was imprisoned a number of times for condemning the violence perpetrated by the Pakistan military. Abid Zubairi, another NAP leader, who opted for a peaceful settlement of problems with Bengalis, avoided arrest by going underground, adds Qazi.

Qazi also informs about Hameed Akhtar and Abdullah Malik, who were both journalists as well as members of the (underground) Communist Party of Pakistan. “They worked for various newspapers including the Pakistan Times and the Azad. Both were imprisoned for supporting the Bengalis' struggle against exploitation. Abdullah Malik was sentenced to forty lashes by a Martial Law court for writing an editorial in favour of Awami League,” he says.

Other communist leaders and party members who were subjected to torture and harassment include Eric Cyprian, Amin Mughal and Comrade Imam Ali Nazish Imrohvi. Professor Cyprian and Mughal were fired from their job and arrested and tortured for taking out a procession in Lahore against the military operation while Comrade Imam, Secretary General of the Communist Party, went underground to avoid arrest. However his house was searched and his family members were picked up by the martial law authorities on hearing that his party was fomenting public agitation against the atrocities in East Pakistan, according to Qazi.

| |

|

Sindhi nationalist leader GM Syed was one of the few who openly supported the struggle in East Pakistan. Another Sindhi leader who remained loyal to his party even in the turmoil was Qazi Faiz Mohammad, Senior Vice President of All Pakistan Awami League, informs his son Javed Qazi. An obituary about his father in the Urdu daily Jang written by notable Pakistani writer Ali Ahmed Rushdie mentions, 'When it was appearing that Sheikh Mujib will form the government, all opportunists joined Awami League, and when it became clear that the operation will start against them all ran away but this man (Qazi Faiz Mohammad).' Javed Qazi adds that a joint statement by his father and the then Awami League leader of North West Frontier Province leader, Master Khan Gul was jointly published in the daily Jang condemning the military operation.

Even Awami League (West Pakistan)'s office bearer was not left alone by the military regime. Mohammad Khan Raisani office bearer of the party in West Pakistan was taken into Martial Law custody after the beginning of the infamous Operation Searchlight and underwent severe torture, informs Usman Qazi.

Unlike the statement of Qazi Faiz Mohammad and Master Khan Gul, Waris Mir's article series on the genocide of East Pakistan could not see light in 1971. Waris Mir, professor of journalism in the University of Punjab, Lahore, and also the adviser of the student affairs, had proposed that students visit East Pakistan instead of Turkey or Europe with the Vice Chancellor's fund released a few weeks after the crackdown, informs Hamid Mir, prominent journalist, executive director of GEO Television, Pakistan and son of Waris Mir. “They reached Dhaka and spend some time in Dhaka University and also met some victims of the genocide. When my father came back, students addressed a press conference in Lahore against the genocide but no newspaper published the story,” says Mir. Later his father's experiences were published in the chapter titled "Sakoot-e-Dhaka Sai Chanbd Haftey Peshtar" from a compilation of his intellectual work "Waris Mir Ka Fikri Assasa".

Many retired Pakistani Army officials still criticise the military actions taken by the Yahya regime and welcome Bangladesh's initiative to try the war criminals. One of them is Air Marshall Asghar Khan, renowned in Pakistan for his democratic viewpoints and outspoken nature. Being an adherent democrat, Asghar Khan wanted power to be handed over to the elected representative Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, in the 1970 election. “However, when he met Bhutto and sensed his intentions, he had told him, 'From today I shall stand against you',” narrates Shahriar Kabir, who met the veteran soldier in Pakistan.

The first procession that was brought out in West Pakistan in protest of the killings in the then East Pakistan was led by human and women rights activist Tahira Mazahar Ali along with Nasim Akhter. Tahira told Kabir how they had arranged a small gathering of female garments worker in front of the District Magistrate's office at Lahore, with handwritten-cyclostyle placards, condemning the genocide. Their non-violent protest was dealt with harassment and arrests by the military government.

United Nation's human rights rapporteur Asma Jahangir's career started at the eve of Bangladesh's birth. A young woman of 18 and not even a lawyer yet, she challenged the legality of her father, Malik Ghulam Jilani's arrest. Jilani, a distinguished member of the ruling elite and a legislator in Pakistan's National Assembly, was detained because of his support for the East Pakistan. When no lawyer dared to defend Malik Ghulam Jilani, Asma came forward and challenged the legality of the marshal law regulation by Yahya government that issued the arrest warrant. To date the case fought by Asma Jahangir remains a landmark in Pakistan's legal history.

While Bangladesh celebrates the 40th anniversary of its glorious victory, we remember with gratitude all those friends around the globe, who in our most dire time, stood beside us daring all odds. This article may have mentioned only a few of the many friends of Bangladesh in her struggle for freedom however their courage set instances for future generation to raise their voices against injustice and violation of human rights.